![]()

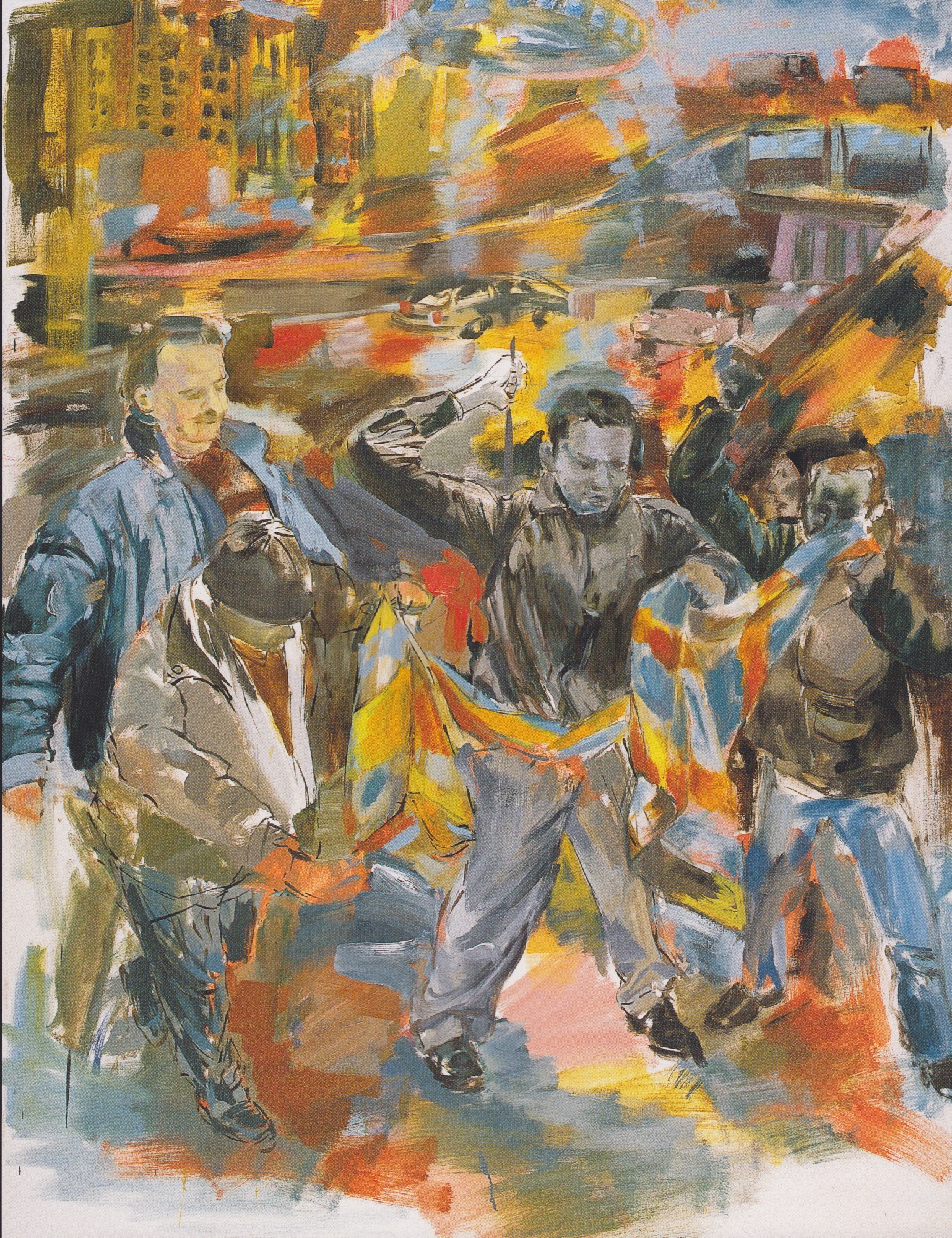

carpet wars / oil on canvas / 140 × 200 cm, 2003

carpet wars / oil on canvas / 140 × 200 cm, 2003

HOW TO ESCAPE LEGITIMACIES – THE PAINTINGS OF MUSTAFA PANCAR

Emre Zeytinoğlu

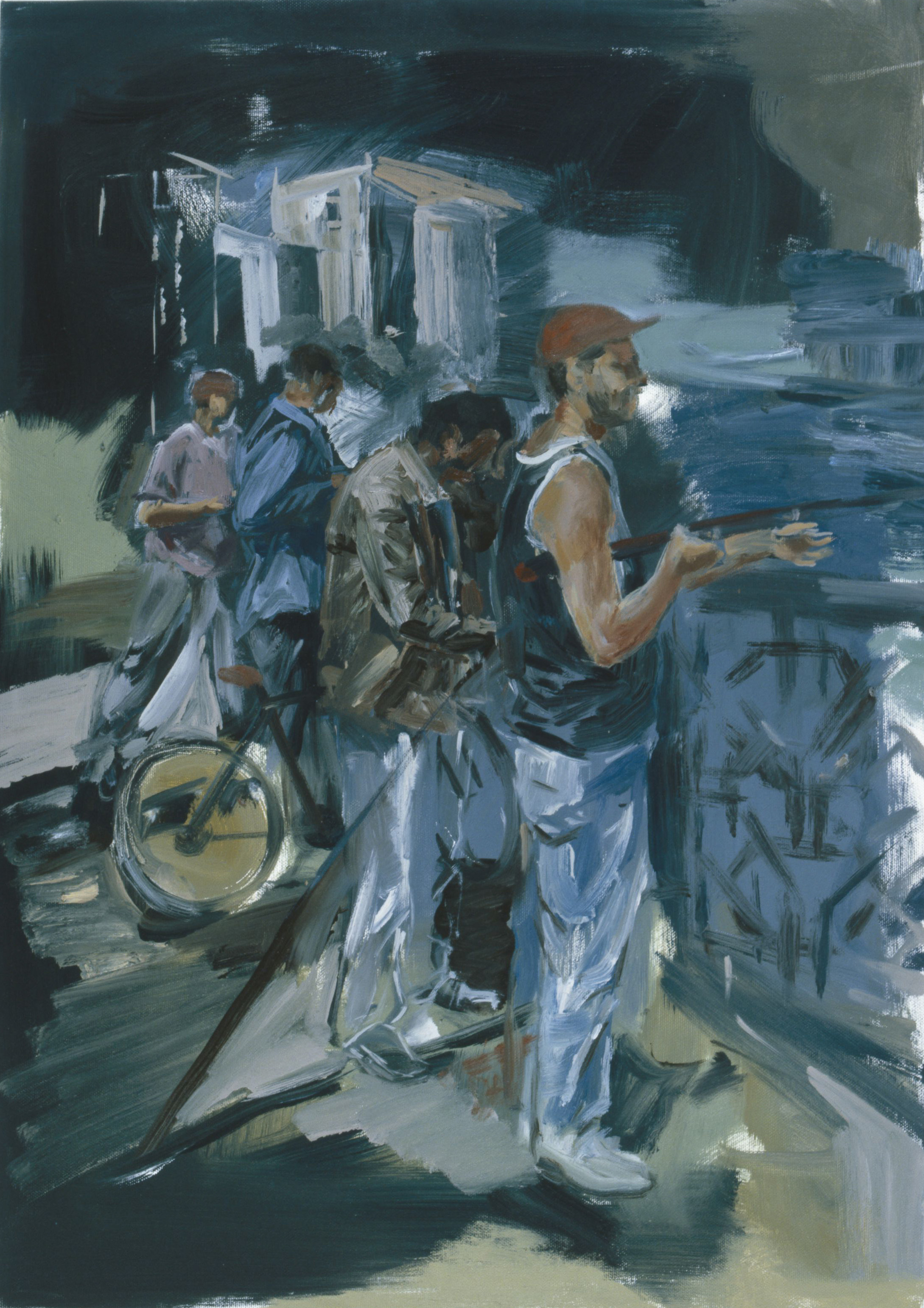

watch out for your wallet – before the EU / oil on canvas / 115 × 148 cm, 2003

watch out for your wallet – before the EU / oil on canvas / 115 × 148 cm, 2003

![]()

carpet wars / oil on canvas / 140 × 200 cm, 2003

carpet wars / oil on canvas / 140 × 200 cm, 2003

HOW TO ESCAPE LEGITIMACIES – THE PAINTINGS OF MUSTAFA PANCAR

watch out for your wallet – before the EU / oil on canvas / 115 × 148 cm, 2003

watch out for your wallet – before the EU / oil on canvas / 115 × 148 cm, 2003

HOW TO ESCAPE LEGITIMACIES - THE PAINTINGS OF MUSTAFA PANCAR

When King Karl V went to war in Tunisia in the year of 1535 he didn't only have his army beside him. The King had included many European painters in his entourage; he had wanted the war to be depicted in all its various aspects. Throughout the protracted siege the painters had the opportunity to be acquainted with the Ottoman army, the people, their lifestyle and the places they lived in. The sketches drawn from these observations (with the inclusion of various fantastic features developed about the East to these drawings) would then transform into huge Gobelin tapestries in Venice and the depictions of war would at the same time become documents of the imagination the Westerner developed about the East.

Mustafa Pancar came across these Gobelin tapestries exactly

468 years after the war in Tunisia at the Vienna Museum of Art History; and the meaning he ascribed to them was quite different either from that of the Venetian palaces, or the Viennese museum. It was impossible for Pancar to look at these images with a Western perception; he was not a Westerner constructing the East in his mind through these works of art. What’s more, he didn't resemble the Easterner in the imagination of the Westerner, he failed to recognise the fanciful depictions before him and he had trouble combining his own life-experience with what he saw at the Museum. Therefore, once he set out to observe the Gobelin tapestries at the museum, Pancar would neither need to take sides between East and West, nor could he be seen as the product of Orientalism, which began to demonstrate an identity and definition of its own towards the end of the 18th century. The only way he could act was to look at these images from a distance' with absolutely no prejudice or sense of belonging... That is exactly what he did; he took out his drawing materials, he positioned himself before the Gobelin tapestries and quickly made pictures-of-pictures in his sketchbook. His sketches were not copies by any means; thus he did not intend to register the model he had failed to imbue with meaning. If the gobelin tapestries in the Museum lose their meaning the moment when, in Pancar's mind, the identities of Easternness and Westernness are muddled, the sense of belonging is blunted and oppositions are erased; Pancar's sketches would then emphasize this loss of meaning and the distance that he would set between them and himself. That is why the painting entitled 'Carpet Wars' is not a general interpretation (or contra-interpretation) of the Gobelin tapestries, but a brand new work, of which Pancar made the preliminary sketches at the Vienna Museum of Art History (Although Pancar's approach, which restrains from copying the Gobelin tapestry untitled 'Dor Tunis-Soldzug Karl V' literally might, in a way, remind us of Jan Cornelisz. Vermeyen's approach in depicting the Ottoman War shows the difference between the artist's and the approach to the problem of belonging and separates them) Pancar, in his work entitled 'Carpet Wars' demonstrates the distance he creates between himself and what he sees, by moving away from the model. In this work there are two different dimensions to the method of 'moving away from the model'. In the first dimension, the images on the Gobelin tapestries have been rearranged and the semantic ties between the figures have been transformed into a different story altogether for example Pancar depicts Vermeyen, who is watching the vast battlefield from a higher ground, among war scenes and appears to cast him as a war journalist. Here, the fact that Pancar does not have any interest in copying or interpreting the work of the painter of war is further accentuated. By introducing the painter of war into the painting itself he carries the meaning of the Gobelin tapestry from the vision of the 16th century to 'the vision of today' (his own vision) and disconnects it from the traditional imagination of the West. In its second dimension; there is a physical inter-space between this redrawn Gobelin tapestry and Pancar. In Pancar's painting we see the Gobelin tapestry of the painter of war from afar. The Gobelin tapestry has been rather enlarged and even blown up to a comical extent in Pancar's work (This approach is somewhat reminiscent of Kafka's approach, when instead of hiding severe oppositions he enlarges and exaggerates the forms, which constitute these contradictions. According to Deleuze and Guattari, this was how Kafka managed to remain outside all dualities and succeeded in cleansing himself from the cultural protection of legitimate and major political views). We perceive the wall of the museum, the flooring and the seats surrounding the Gobelin tapestry at the same time. Thus, the Gobelin tapestry Pancar transfers to his own work is both physically remote to us and what’s more, the time of the Gobelin tapestry unites with the time of the museum space surrounding it (Indubitably, the time of the museum space is exactly the time when Pancar is present in it, the context of the image we see, connects not with the war in Tunisia or the depiction of it, but with the Museum space where that depiction has been installed). 'Carpet Wars' is a painting, which revolves both between East and West; and between Pancar, who is unable to adapt to any duality and the dualities the painter of war proposes; it never reaches a definite judgment...

Pancar, who fits Jan Cornelisz. Vermeyen's eye and his own vision within one another (thus canceling both) appropriates the same method in the other works in the exhibition. For example, in the work entitled 'Welcoming and the 'Observation of Nature' the artist again uses both his own gaze and the gaze of a figure placed within the work. Here the work adopts an official welcoming ceremony as its subject matter. However, the ceremony is not transmitted to us by the painter but by the frames of the figure in the picture appearing on the video camera (we do not fully see that figure). Yet, while the painter physically distances himself from the event (the model) he paints, at the same time he places himself before the model by having actually painted that video camera. This is the suspension of the meeting with and the distancing from the model, or of any decision we are to make about the reality of the event we are viewing.

The reason Mustafa Pancar appropriates both his own gaze and the eye of the other 'the external eye' in his works at the same time, maybe because he prefers only to be a distant 'conveyor of events'. He may be, at first sight, a passive intermediary conveying events 'second-hand', but to ensure this passivity, he reciprocally disrupts both his own conclusions and the conclusions of the 'external eye' he places within his work. This is where Pancar's effectiveness lies (what Pancar does is to 'escape' or 'withdraw' from the grand narratives and from their strict forms; so here we may recall Kafka once more). In this context, the painter creates even 'an alien fantasy' with the mediation of that 'external eye'. In the work entitled 'Aliens' we encounter a design of an alien, which only the most primitive imagination might propose. The figure of the alien is reminiscent of the human figure, but differs from the human being in its mechanical construction. It wanders among people on earth, approaches the door of the artist's studio and whatsmore, rides a bicycle. This is an alien developed as far as the 'alien' conception of the 1950's or one might prefer to say 'absolutely underdeveloped since then). Here too, the alien is not the design of the artist. The work shows a crew filming a series in the street and the alien figure is shown as the fantasy of that crew. Hence Pancar paints the design he disdains by somewhat enlarging it and at the same time by removing himself from his own work transforms himself into the 'conveyor of events'. To rephrase; the events are determined by the painter, no interpretation or judgment is brought upon the events, yet the images imposed upon the 'external eye' are enlarged (again by the painter): He is neither the one who designed the alien, nor the one who didn't, neither the one who certifies it, nor the one who doesn't; he is solely the one painting the alien (and the film crew surrounding it) from a distance.

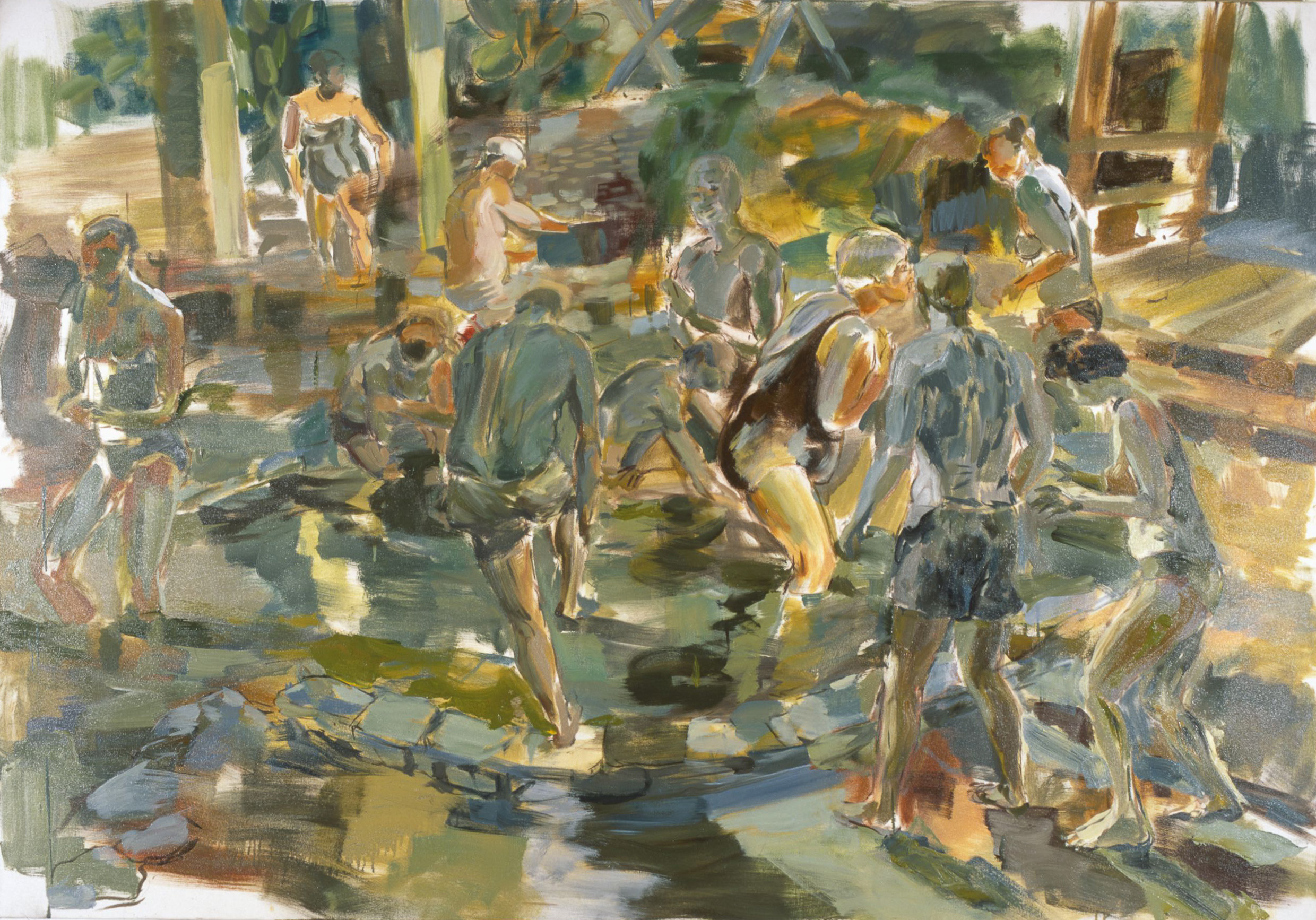

Pancar, in his works at the exhibition, creates all the events (as he did at the museum in Vienna) by maintaining his distance with himself. This distance is at times produced by appending a space into the painting (as with the museum space, which is not a part of the Gobelin tapestry, being included in the image, the observation of the welcoming ceremony from the image appearing on the video camera and the alien being presented as the fantasy of the television crew). Sometimes this inter-space does not enter the picture, and the artist acts as if he witnessed the event in passing. These images remind us of photographs which we glimpse (but do not read the captions of) while we quickly flick through the pages of a newspaper. For example, the paintings entitled 'The Fishermen', 'Mud Bath' or 'The Family Watching a Rally' are also like pictures-of-pictures from newspapers.

Finally, let us not pass without pointing out the following:

Although this exhibition takes its name from the works called 'Carpet Wars' and 'Aliens', the artist only shows us one work on each of these subjects. To put it clearly; when deciding on the name of the exhibition Pancar did not take heed from an event challenged extensively in this exhibition (or from a thematic unity of of the works). He rather, like the approach adopted with a CD or a book of short stories, chooses how works from among many and brings them to the forefront. Is this an 'evasion' of the necessity of the exhibition 'being named' or does Pancar view his own exhibition also 'from a distance'?

The fact that the painter views his own exhibition from a distance is a sign of his indifference towards 'the great purposes' assigned to art.

Emre Zeytinoğlu